The controversy behind poll accuracy, explained

Recent elections have raised controversy over whether polls really can accurately predict outcomes. Here’s what we found out about this hot topic.

Election polls are more than just numbers and percentages.

January 12, 2021

The results of the 2016 election came as a surprise to both Republicans and Democrats. Almost all polls predicted Hillary Clinton to beat Donald Trump by a landslide. Even on Election Day, November 8, 2016, polls nationwide were still declaring that Clinton would become the first female president in United States history. Clearly, this wasn’t the case when it came to calling the race early the next morning.

Key battleground states in 2016 such as Florida and Michigan were a surprise to voters from both parties. Trump had a big win in Florida by about 100,000 votes, while Michigan, a traditionally blue state, turned red by about 13,000 votes. Both states were originally predicted as a win for Clinton.

These turnarounds have raised major controversy for future elections and have made many Americans, including myself, ask an important question: are polls accurate?

Going into Election Day 2020, democrats were considered to have an advantage as they had a significant lead in Florida, a swing state that could potentially decide the election. Many predicted that the Sunshine State would go for Biden. Although Barack Obama won the state in both 2008 and 2012, Trump won Florida in 2016.

It could have gone either way. Even though many were on edge throughout the process, including myself, Florida’s 29 electoral votes ultimately went to Trump as he defeated Biden by about 400,000 votes in Florida.

Obviously, the polls predicted some traditionally blue and red states correctly, but some states didn’t act as expected.

For instance, although few predicted Arizona would go red in 2016, it’s 11 votes helped Trump win the presidency. In 2020, Arizona surprised the nation again by going for Biden.

Texas, a traditional Republican state, was speculated to be a tight race this election with a chance of Biden taking the lead. But in the end, Texas was a win for Trump by nearly 600,000 votes.

Many would think that after the 2016 polling disaster, pollsters would have learned from their mistakes.

The inaccuracy of polling partly has to do with voters not revealing who they support when asked who they are going to vote for. Some polls from major news organizations are based off of the data from people chosen at random to be interviewed via a phone call.

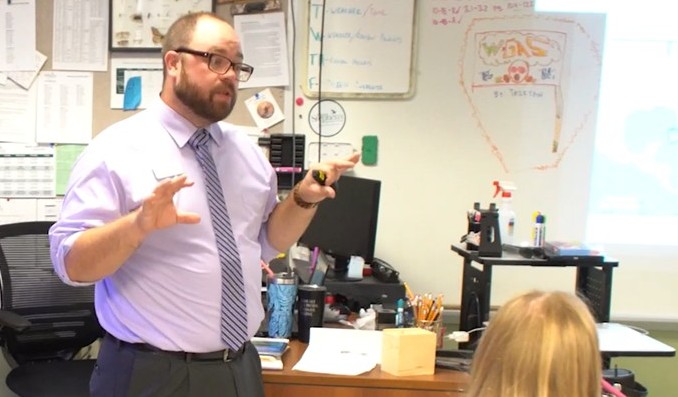

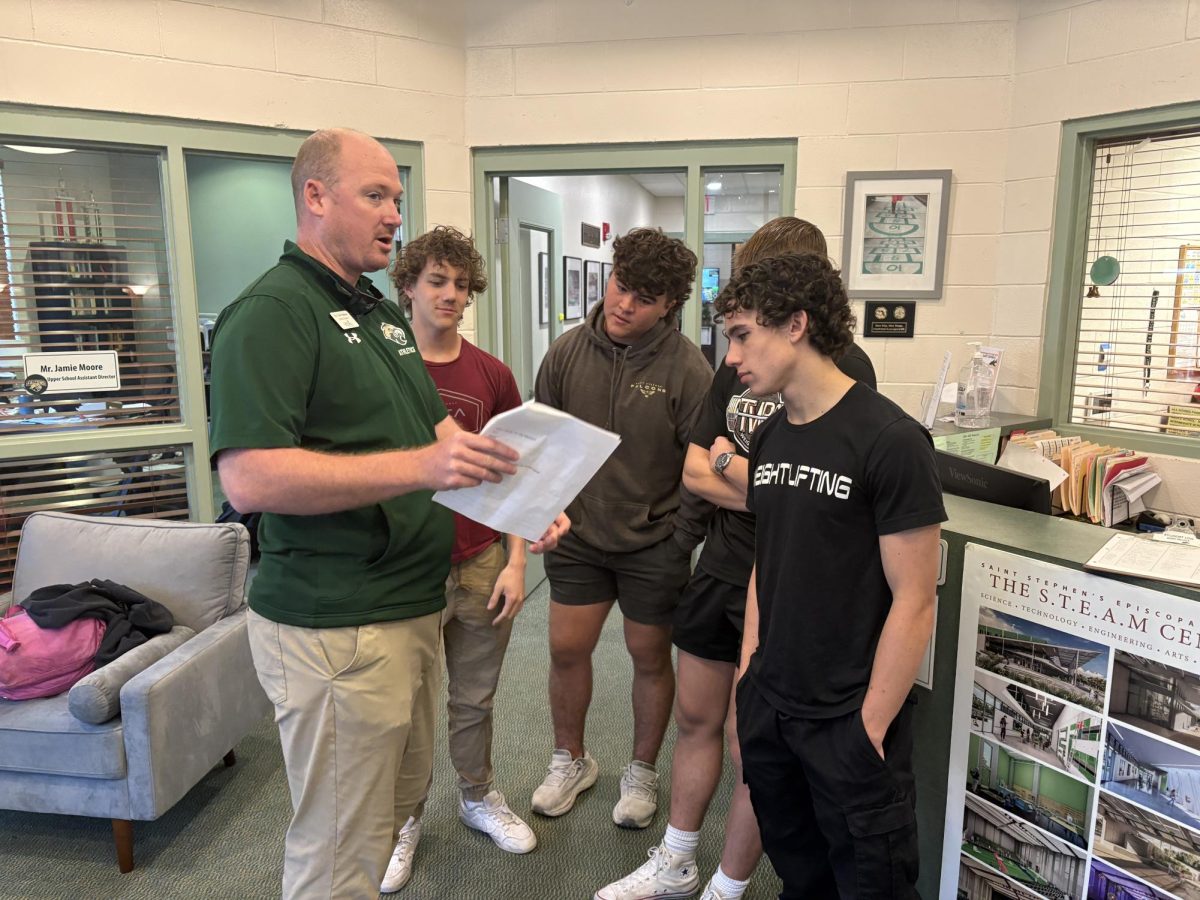

According to history teacher Mr. David Ruemenapp, these sudden phone calls often leave the interviewees hesitant to voice their true opinions. “The polling that is done over the phones is less reliable, I think, because people are either less likely to answer a random number or believe that their information is somehow being monitored as they answer polling questions,” he explained. “…It doesn’t give you as random a view as it has in the past and likely skewed some of the results.”

When it comes to discussing politics, some people won’t be as forthcoming about who they voted for than others, especially towards a complete stranger.

This can make it extremely difficult for pollsters when making their predictions. When confronted directly, a Trump supporter may not reveal that they are actually going to vote for Trump. This may be partly the reason why the polls were so inaccurate in the 2016 election.

2020 saw record voter turnout with about 160 million votes cast, more than any other election in American history. This also played a major role in the projections, since usually only around half of eligible voters actually cast a ballot.

Polls also project the winners of other smaller government elections. It seems that in these smaller elections such as the senate races, pollsters have better luck with predicting the winner.

In South Carolina, incumbent republican senator Lindsey Graham was running for reelection against Democrat Jaime Harrison. Polls had Graham and Harrison on very close margins with each candidate going back and forth as the frontrunner. In the end, Graham beat Harrison by nearly ten percent.

Similarly, in Kentucky, senate majority leader Mitch McConnell was running for his reelection against democrat Amy McGrath. Many said this would be a tight race but it was still projected that McConnell would win by a margin of at least ten percent. Once the race was called on election night, McConnell beat his opponent by nearly twenty percent.

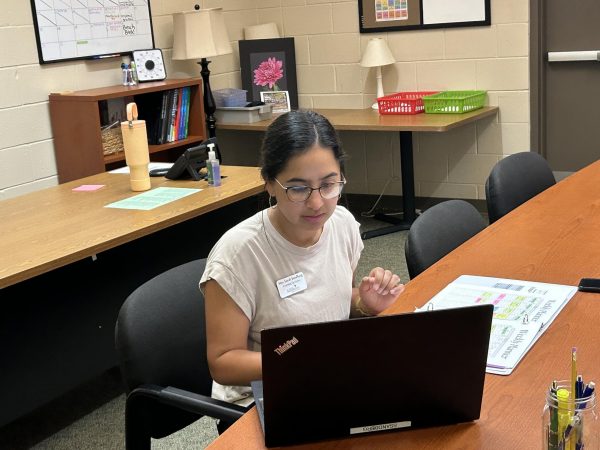

While there’s no easy solution to this problem, one way that some have proposed to possibly make predictions more accurate is to ask them how they think others will vote, rather than who they personally will vote for. Not only does this give news outlets an idea of what a potential state demographic could look like, but also alleviates some of the pressure surrounding on-the-spot interview questions. This may help pollsters get a more accurate idea of how those in a particular area may vote without having an individual hiding their views or just saying what they think people will want to hear and end up not giving reliable information.