What it means to be a writer

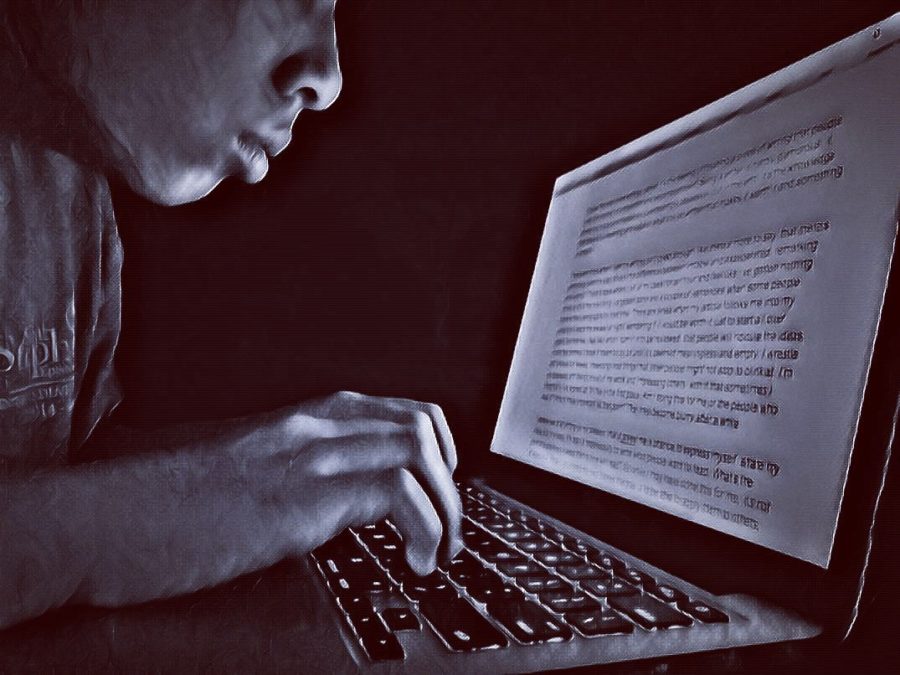

You’d expect any passionate writer to be typing at their desk nonstop, letting the inspiration flow. But that’s not exactly how it works. It’s time to get real about what actually happens behind the “screens” of most writers.

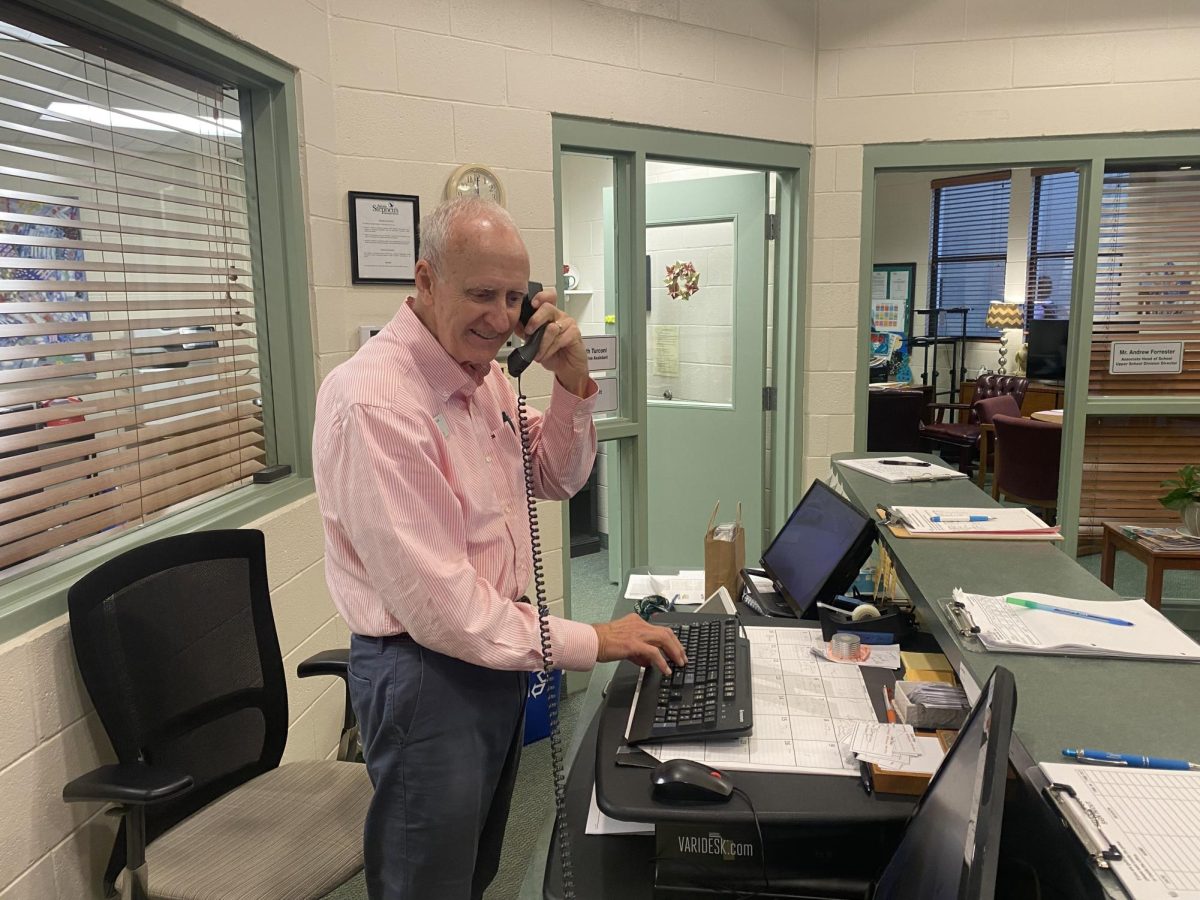

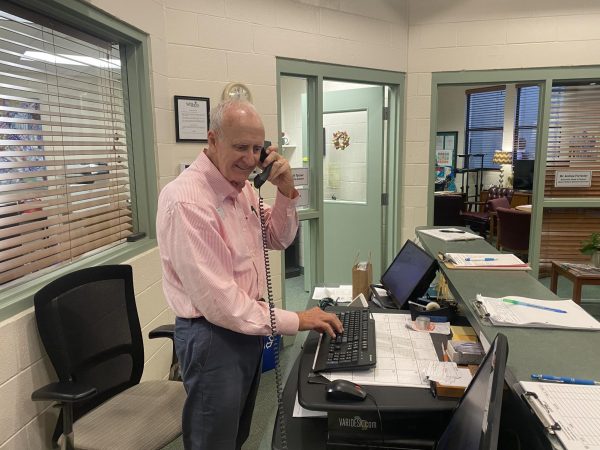

For many students, staying up late to finish an essay is not uncommon. For The Gauntlet staff writers, it’s no different.

When people hear I’m a member of The Gauntlet, chances are they’ll assume one of two things. The first is that I’m just another writing geek. The second is that I took it as an opportunity to catch a break from droning lectures throughout the day. While the latter may seem more likely to most students, I’ve repeated the same three-word phrase to explain my reasoning time and time again:

“I love writing.”

A part of me wants to stay true to this phrase for the sake of simplicity. I love to write. Simple as that. But the other part, the part that never stops asking questions and having doubts, tells me that this might actually be a lie, one that I’ve been telling myself–and others–for years. The biggest problem I have with this phrase is that on the surface it screams, “I enjoy locking myself in my room for three hours to stare at my laptop.” So no, the truth is that I don’t “love writing”; rather, it’s the experience I get after it’s been completed.

I would largely agree with The Guardian‘s Tim Lott that the notion of a writer’s role is, more often than not, highly “romanticized”. I bet that everyone can name at least one instance they’ve seen of a cookie-cutter portrayal of the writing process in media. In movies, the common author’s trope is that of a figure whose inspiration comes spontaneously from some arbitrary, “magical” source (and in Lott’s case, that happens to be “staring wistfully out the window”). The next thing you know, a lightbulb goes off in said author’s head. A theatrical montage of the wordsmith typing away at their computers until an ungodly hour of the night ensues. The following morning, they triumphantly slap down a masterpiece on the editor’s desk, likely with a horrible bedhead and a crooked tie. Sound familiar?

But anyone who has ever written a lengthy 1,000-word essay knows that this is never how it plays out. Writing never takes a linear start-to-finish path. It never comes out exactly the way you want it to be, no matter how many times you cut, copy, paste, or crumple it up and start again. What’s more, it’s a horrendous mess of coming up with a whole list of ideas and only using one. An endless torrent of running around in circles; of pacing up and down halls; of hair-pulling and staring blankly at walls until your brain goes numb; of spending mindless hours brainstorming and outlining that will, in the end, only lead you back to square one.

While I doubt any of us staff writers are going to be the next hottest columnist on The New York Times, we all have hope that there are those on the other side of the screen, ever-willing to digest what we have to say.

With that said, it may come as a surprise when I tell my readers that I break pretty much every glamorized writer trope out there. Finding inspiration can be like searching for a needle in a haystack: coming up with a solid idea sometimes takes me up to a full week, and writing up a draft, often two. Given that most of my articles are no longer than 800 words each, you might start to question if I’m using my time effectively, to which I would answer both yes and no.

Fun fact about me: I’m wildly obsessive when I want to be. I will read the same paragraph over once, twice, three times. I will backspace, rearrange, and ponder well after sundown. I will break it down bit by bit until I somehow lose what I’m really trying to say, and then return to it the next day only to begin the cycle all over again.

But once that storm has passed, I sit back in my chair and look at the work that I’ve spent weeks mulling over, and it reminds me why I’ve chosen to call myself a writer in the first place. There, in front of me, is something that I created essentially out of nothing; what started as a blank slate is now filled with something meaningful, something that others can relate to. No matter how dissatisfied I am with the final product, I at least know that I did my job: that I created something worth reading. And that, in my book, trumps any notion of perfection.

So while I doubt any of us staff writers are going to be the next hottest columnist on The New York Times, we all have hope that there are those on the other side of the screen, ever-willing to digest what we have to say. Because of this, we put our best foot forward each and every day.

No one is expected to produce a magnum opus when they settle down to write a term paper or an article. Nor are they expected to be as prolific of a writer as, say, Alexander Hamilton, who completed 51 essays in six months. But even so, let’s not waste our words. We are all capable of far more than what we give ourselves credit for. We can all write something worth reading.

Do your worst, writer’s block. We can all face you head-on.

1

Codie Moss • Apr 18, 2019 at 2:15 pm

Jules,

I love this piece! You did a great job writing this!

-Mrs. Moss